What can we learn from the ‘Anthropause’?

The Covid crisis has turned our world upside down. After months of complete shutdown and subsequent slow re-opening, a second wave might be on the way. But while nobody knows what the future will bring, wildlife biologists examine which influence the lockdowns have on wild animals. Some of the consequences were already visible early on. Deer and monkeys roamed the streets in Asian metropolis. In Europe, many of our followers spotted animals in places, where humans normally spend their free time. So, now researches want to know if these sightings are just isolated cases or if animals changed their movement patterns during the ‘Anthropause’.

Which effect did the anthropause have on wildlife?

In a comment, a group of researchers emphasized the uniqueness of this opportunity and named it the ‘Anthropause’ or ‘Great Human Pause’. They propose “anthropause to refer specifically to a considerable global slowing of modern human activities, notably travel.” To seize this opportunity, they call for collaborative intitiatives to research the effect of the anthropause. The SARS-CoV2 virus showed us that human and animal welfare are intertwined and the exploitation of our natural resources can cause catastrophes. Understanding the interactions of human and animal behaviour can help to develop new strategies for human wildlife coexistence and prevent damage. This is also key to protect biodiversity and mitigate climate change. Possible results include knowledge which species are most affected and threatened by human activity and which species respond well to sudden changes. This could help define thresholds of human activity, above which wildlife is seriously stressed.

Please also read: As countries go on lockdown, nature goes wild

The effects of the anthropause go much further than a few animals sighted in cities. Decreased traffic and mobility on land, water and in the air has reduced light and noise pollution. On the other hand, many people tried to spend as much time as possible in green spaces close to their homes, which could distract resident wildlife. And the absence of tourists, rangers, and conservationists made poaching easier in many protected areas, while the lack of tourists increased financial pressure.

Reduced human mobility during the pandemic will reveal critical aspects of our impact on animals, providing important guidance on how best to share space on this crowded planet.

Unique opportunity for research

While the effects of human presence on wildlife have been studied before, such a ‘controlled experiment’ in unparalleled in history. Researchers either had to study populations in areas with different human activity, which introduces a lot of other factors. Or they find to find single spots, where human activity changes over time. The worldwide series of lockdowns created a new scenario, where human activity diminished suddenly and widespread around the globe. Using these unique circumstances, researchers could use a pool of many datasets to create a global picture. Following the call, scientists have already made over 200 datasets on over 150 species available.

A first step towards this vision is the ‘COVID-19 Bio-Logging Initiative’. It unites researchers using ‘bio-loggers’, small devices attached to animals that record behaviour, movement, activity, environment or physiology. These “biologists that studied their chosen study species, put tracking devices on animals, and then COVID-19 happened. Nobody saw that coming. But these devices kept delivering data. And now in this period of crisis, all these colleagues have decided, rather than pursuing their independent research projects, it’s better to pull resources together and do these global collaborative analysis” (Christian Rutz). The first project is to compare old data with data from the anthropause to examine whether built structures or human presence determine the movement of animals.

These initiatives provide valuable platforms for wildlife biologists, human mobility researchers, bioinformaticians and other experts, to join forces for ambitious large-scale analyses. This crisis, and the unique research opportunities it affords, demand such collaboration, as well as full transparency and effective coordination.

The anthropause is not over yet

Even though lockdowns have been lifted all over Europe, the anthropause is not over yet. The pandemic is still raging around the world and mobility is still nowhere close to pre-covid levels. Hence, it is crucial to continue collecting data on this event. The authors of the comment give some practical recommendations to fellow scientists and other stakeholders to make the most out this situation:

- Biological field work must be possible despite restrictions.

- Human activity and official restrictions should be recorded for study areas.

- Scientists willing to participate are encouraged to contact larger initiatives as soon as possible to coordinate research on a global scale.

- Formation of partnerships to make high-quality data on human activity available for initiatives.

- Funding for follow-up studies is required to compare data from before, durign and after the anthropause.

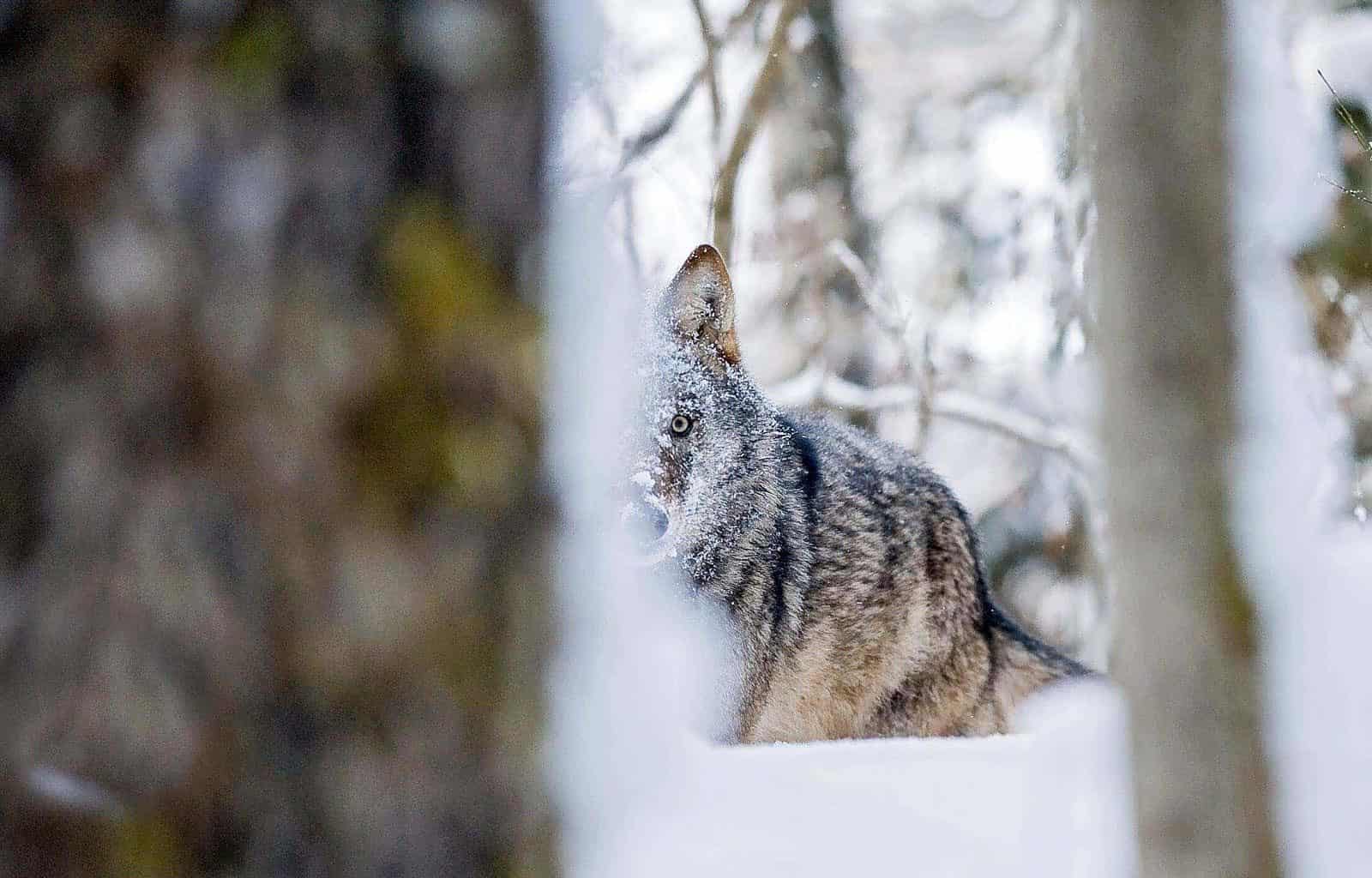

The only event in recent history comparable to the anthropause is the Chernobyl disaster. The meltdown of the nuclear plant forced all humans out of the area from one day to the other. It also killed most of the wildlife present. But with radiation dropping rapidly within the first years, wildlife soon returned, while the 30 km wide exclusion zone is mostly free of humans. Instead of rats and pigeons, this zone is now inhabitated by deer and wolves. Even though the Covid-crisis will not have such a long-term impact, it will be interesting this long-term, but local anthropause to a global, but short-term pause.