Re-Connecting Wilderness

Nowadays, there are many threats to the connectivity of landscapes. Despite the importance of connecting protected areas, that was outlined in a recently released report in the Nature Communications Journal, the world currently only has 9.7% of sufficiently connected intact areas. The most common threats to connecting protected areas are agriculture, urbanisation, mining and unsustainable forestry. These processes consequently disrupt the connectivity of landscapes. For example, urbanisation has led to many threats that affect mammals in adverse ways. “Roads, railways, human population density, built environments, night-time lights and navigable waterways” are just some of the threats to mammal movement, behavioural diversity and survival quoted in the report on global protected area connectivity.

Please also read: Mitigating the Disintegration of Wilderness

Moreover, these obstacles pose a threat to the establishment of new connections between protected areas. In order to overcome these hurdles, re-wilding helps by enabling the creation of connections between protected areas.

The Fight Back

Alongside rewilding, other strategies are key to getting the most out of structural connectivity. On a practical level, there is a need for a better placement of future protected areas and other area-based conservation efforts. This will include restoring natural habitats beyond protected area boundaries, in order to allow for bolder habitat retention and the achievement of wider landscape and regional scale connectivity outcomes. However, the restoration of natural habitats is not just about the number of organisms protected, but about the types of habitats and the species that will be protected, especially threatened species and those that are native and restricted to a certain place.

Social and political considerations are also relevant when it comes to increasing structural connectivity. Most importantly, the report states that preserving intact areas and increasing their connectivity requires their formal recognition, social acceptance, prioritisation in spatial plans, while also being economically viable and effectively managed so that they can be protected from human impacts.

Only nine countries and territories have over 17% of their land protected and maintain over 50% structural connectivity between their protected area sites. This is despite many governments having their protected area targets at 17% of national land. Therefore, action on biodiversity requires a more concerted governmental effort , to the scale that has been seen on climate change. Crucially, there is a chance to work towards this at COP15 of the CBD in 2021, to try and enact legally binding targets for the next 10 year strategy period, that build on the current Aichi Target of 17% of protected terrestrial areas.

Current Measures

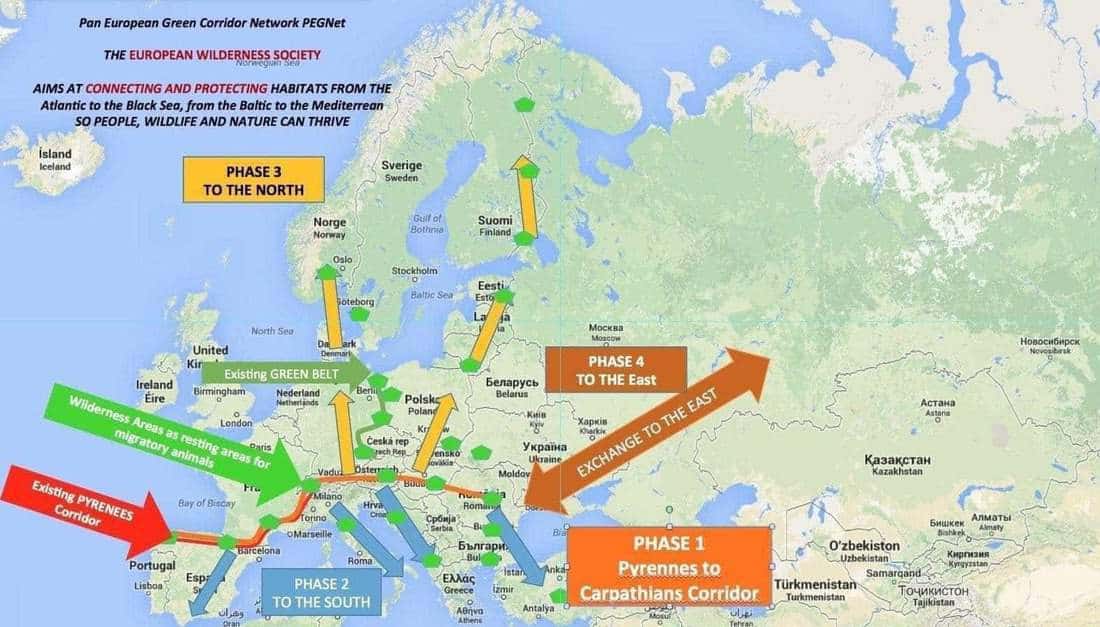

The EU have made efforts to address this issue in its 2030 Biodiversity Strategy. The European Commission has adopted the target of protecting 30% of land and marine areas. Of importance to these efforts is the Trans-European Nature Network. This network aims to create a landscape that allows the natural functioning of ecological processes and enhances biodiversity. Such a network requires the establishment of green corridors to enable migration and gene flow across Europe. The European Wilderness Society has previously suggested a strategy for a European green corridor network, the Pan-European Green Corridor Network. Such networks provide opportunities to reconnect natural areas in Europe with the aid of Wilderness areas and Natura 2000 sites. Above all, these sites support migrating animals by offering resting and mating areas.

Globally, the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration starts in 2021. This aims to restore 350 million hectares of degraded land between 2021-2030. Hopefully, this will result in improved connectivity between protected areas, creating a more resilient landscape for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Another chance to improve structural connectivity presents itself at the COP15 of the CBD in 2021, where the next ten year Strategic Plan for Biodiversity will be agreed on. In relation to that, scientists proposed the ‘Three Conditions for Nature’ Framework to the CBD. This framework divides terrestrial areas based on land-use drivers and pressures. The three categories are cities and farms, shared lands, and large wild areas. Findings in the Nature Communications report state that, unsurprisingly, the greater proportion of large wild areas a country has, the higher their proportion of connected protected areas. Wilderness areas and the restoration of natural areas are thus key in improving the effectiveness of protected areas and connectivity.

Future Resilience

To sum up, better connected protected areas have many benefits to both nature and humans. Increased structural connectivity will improve ecosystems’ ability in fighting climate change. This is because it allows for the large-scale ecological and evolutionary processes to continue. With more Wilderness areas, which are free from human intervention, ecosystems and their organisms will have more space to adapt. In addition, this reduces the impacts of climate change, such as large extinction events and loss in biodiversity. More resilient ecosystems, brought about from better structural connectivity, can help tackle the world’s most pressing contemporary challenges.